27 Years Ago, Steve Jobs Said the Best Employees Focus on Content, Not Process. Research Shows He Was Right

According to the Apple co-founder, the best employees are also a pain in the butt to manage.

In 1979, Steve Jobs and a number of Apple engineers and executives visited Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), a research center designed to develop new technologies and products. That's where Jobs apparently first saw the mouse, windows, icons, etc.

Jobs spotted an opportunity. "I got our best people together," he said, "and got them working on (Apple's version of a graphical user interface)."

But it didn't go smoothly. According to Jobs:

The problem was, we had hired a bunch of people from Hewlett-Packard, and they didn't get this idea. I remember having dramatic arguments with people who thought the coolest thing was having soft keys at the bottom of the screen. They had no concept of proportionally spaced fonts. No concept of a mouse.

In fact, I remember folks screaming at me that it would take five years to engineer a mouse, and it would cost $300 to build. I finally got fed up and went outside and found David Kelly Design... and in 90 days we had a mouse we could build for $15 that was phenomenally reliable.

Jobs realized "Apple did not have the caliber of people that was necesary to seize this idea... and there was a core team that did, but there was a larger team that... didn't have a clue."

The fundamental problem, according to Jobs, was that many people confuse what he called "process" and "content."

To Jobs, "process" is, yep, process. As a company becomes successful, it tends to assume there is "magic" in the process that led to that success, and it tries to replicate that process. If a cross-functional team created a successful product, hey, let's put together a cross-functional team to develop the next product. If a customer survey generated the idea for a successful service, hey, let's do another survey.

What happens next? As Jobs said:

So they start to try to institutionalize process across the company. Before long, people get confused that the process is the content. That's ultimately the downfall of IBM. IBM has the best process people in the world. They just forgot about the content.

That's a little bit of what happened at Apple too. We had people who were great at management process. They just didn't have a clue as to the content.

Keep in mind "content" isn't what we think of today as content; to Jobs, content was the outcome. The Mac, and its GUI. The iPod. The iPad. The iPhone.

Hold that thought.

The value of truly exceptional employees

Imagine you have 100 employees, and I ask you to graph them in terms of performance.

Most likely, your chart will look like a bell curve: a small percentage of high performers on the left, a few poor performers on the right, and a host of average performers in the middle.

Yet, as Laszlo Bock, the former senior VP of people operations at Google, writes in Work Rules: Insights From Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead:

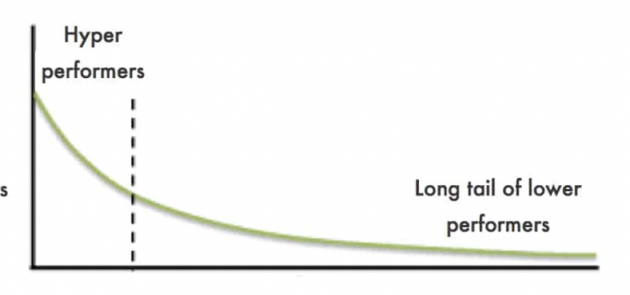

Organizational researchers have shown, similar to the 80/20 rule, the majority of your company's output comes from a minority of "superstar" performers: What's known as a power-law distribution.

In performance terms, think of power-law distribution as a long tail of steadily lower performance. In visual terms, like this.

Other research backs up Bock's position. One study found that superstar employees are three times more valuable than their peers. A McKinsey study found that high performers are four times more productive than average performers. Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings feels the best programmers deliver somewhere between 10 and 100 times the value of an average programmer.

Even so, the standard bell curve underpins most HR systems. According to Bock, that means many leaders "undervalue and under-reward their best people, without even knowing they are doing it." For example, I once rated all my employees as "superior," and for good reason: They were the most productive team in the plant.

HR kicked my evaluations back and said I needed to distribute my evaluations more "fairly."

"Fairly," of course, meant "bell curve."

That caused a few outstanding employees to be undervalued and, as a result, under-rewarded. Since pay was tied to evaluation ratings, they didn't get the raises they deserved. Or the opportunities. (More on that in a moment.)

And that's a real problem. According to a study conducted by SAP and Oxford Economics, 73 percent of high-performing companies place no cap on bonus pay for their best performers, while 81 percent -- the vast majority -- of low-performing companies do.

One result of this is that high performers are more likely to leave their current jobs in the next six months. Because while mediocre employees tend to stay, superstars are always in demand, and always have options.

Think of it this way. "Fair" compensation shouldn't be defined by a job's pay scale. "Fair" is what the employee -- not just the role -- is worth. Great employees are worth much more than average employees to your teams, to your customers, and to your bottom line. Superstar employees are worth dramatically more.

Do what Bock recommends, and pay superstars "unfairly." Pay them not just as if you want to keep them, but as if you desperately need to keep them. Because you do.

Then manage them accordingly.

As Jobs said:

I found that the best people are the ones that really understand the content. (By "content," think what truly drives results in your business.)

And they're a pain in the butt to manage. But you put up with it because they're so great at the content.

And that's what makes great products. It's not process. It's content.

Your best employees aren't the people who excel at following processes.

Sure, you need people who stay within guidelines. Who embrace best practices. Who keep your trains running on time.

Your best people? They're annoyed when others don't contribute. They're frustrated when others don't embrace opportunity. They're dissatisfied with the way things have always been done, because they understand what will truly drive value.

The next time you make a promotion decision, make sure you consider the great individual contributor who, as Jobs said, may not want to be a manager, but desperately wants to get things done.

The next time you make a compensation decision, make sure you consider how much a superstar employee is really worth -- even if (maybe especially if) he or she is also a pain in the butt to manage.

Because success is rarely based solely on process. Success mostly comes down to what your business accomplishes.

Which starts not with whether people simply follow processes, but on what they accomplish.