How are you writing a commit message?

I'll write a little bit about a topic that is not related to code, seemingly not that important, but it is quite practical in daily programming. How to write git commit message properly?

No way of writing is right or wrong; however, if each person in a project has its own style of a commit message, then when we look at the commit history, does it look good? Not to mention when we need to search and review commits in the commit of the previous months through commit messages without any rules.

Commits that are non-consistent in a message format or don't follow any rules can be a problem because of many reasons:

- Reading the commit message without knowing what the exact purpose of the commit was.

- When we need to summarize changes in source code after a period of development (e.g. production release)

- Choosing suitable new version, v1.0.0, v1.0.1, v1.1.0 or v2.0.0 etc.

- Trying to search through commits via regex

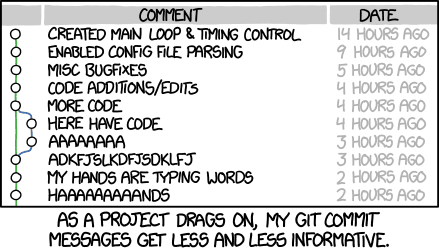

Obligatory xkcd

Some teams decide to implement a kind of closed rules to solve some of the issues caused by fragmented code commit message styles. Why closed you ask? That is because those are local to your project. For example, in my team, we had a convention to prefix commit messages and git branches with the ticket number.

So are there any rules that are common to all of us and can be shared across many projects? Enter...

Conventional Commits

Conventional Commits are a set of commit message writing rules that create rules that are easy to read for both machines and humans. The machines can make use of these rules, for example, in tools for automatic versioning.

This set of rules corresponds to SemVer (Semantic Version) by the way it describes features, bug fixes, code refactors, or breaking changes made in commit messages. Currently, at the time of this writing, this set of rules Conventional Commits is in version 1.0.0-beta.4, and there may be future additions. You can refer to the implementation of conventional commits in some open projects on Github, some of the bigger ones are Electron, IstanbulJs, Yargs and Karma which, if I've understood correctly, actually laid foundations to semantic commits.

The commit message should be structured as follows:

<type>[optional scope]: <description>

[optional body]

[optional footer]

Where:

- The

typeanddescriptionare required by commit message, and all others are optional. type: keyword to classify if the commit was a feature, bugfix, refactor... Followed by the:.scope: is used to categorize commits, but answers the question: what does this commit refactor | fix? It should be enclosed in parentheses immediately aftertype, e.g.feat(authentication):,fix(parser):.description: a short description of what was modified in the commit.body: is a longer and more detailed description, necessary when the description cannot fit one line:

$ git commit -m "feat: allow the provided config object to extend other configs

BREAKING CHANGE: `extends` key in the config file is now used for extending other config files"

footer: some extra information such as the ID of the pull request, contributors, issue number(s)...

Some examples for a short commit message as follows:

# ex1:

$ git commit -m "feat: implement AVOD content reels"

# ex2:

$ git commit -am "fix: routing issue on the main page"

# ex3 with scope:

$ git commit -m "fix(player): fix player initialization"

Semantic Versioning

Conventional Commit matches SemVer through type in the commit message. Automated versioning tooling also relies on it to decide the new version for source code. With the following convention:

fix: a commit of the (bug)fix type is equal to PATCH in the SemVer.feat: a commit of type feature is equal to MINOR in the SemVer.- Also, the keyword

BREAKING CHANGEin thebodysection of the commit message will imply that this commit has a modification that makes the code no longer compatible with the previous version. Like changing the response structure of an API, the handle response part of the previous structure will of course no longer be accurate, and now we need to create an entirely new version by bumping MAJOR SemVer version.

Some common type uses include:

feat: a new feature for the user, not a new feature for a build scriptfix: bug fix for the user, not a fix to a build scriptsrefactor: refactoring production codechore: updating gulp tasks etc.; no production code changedocs: changes to documentationstyle: formatting, missing semicolons, etc.; no code changeperf: code improved in terms of processing performancevendor: update version for dependencies, packages.test: adding missing tests, refactoring tests; no production code change

While these are the most common types that you're going to see in the wild, nothing is stopping you from creating your own types of commits.

Another bonus advantage from using semantic commits is that you can derive a sense of effort from git logs. For example, given below is a year worth of git commits in karma (master branch):

$ cd /tmp/karma

$ git log --pretty=oneline --no-merges --since 2017/01/01 --until 2017/12/31 | cut -d " " -f 2 |\

cut -d "(" -f 1 | cut -d ":" -f 1 | sort -r | uniq -c | sort -nr -k1

39 chore

28 fix

23 feat

15 docs

6 test

2 Try

1 refactor

Using the scope annotation we could further slice and dice this data into questions like which component has the most number of bug fixes?.

Summary

- Commit messages must have a prefix of a type (noun form) such as feat, fix and so on, Immediately followed by scoped (if any), a colon and space.

$ git commit -am "test: add missing tests for promo reels"

featThis type is required to use when adding a featurefixThis type is required to use when fixing a bug- If there is scope, the scope must be a noun that describes the area of the code change and must be placed immediately after type. Eg, feat(authentication). (Examples?)

$ git commit -am "refactor(auth): improve refresh token logic"

- The description must be a short description of the changes in the commit and must be after the type with or without a scope.

- A long commit can have the body right after the description, providing context for the changes. There must be a blank line between description and body.

- The footer can be placed immediately after the body, but there must be an empty line between the body and the footer. Footers should include extended information about commits such as related pull requests, reviewers, breaking changes. Each information on one line.

- Other types than

featandfixcan be used in the commit messages. - Committing breaking changes must be specified at the beginning of the body or footer with the capitalized

BREAKING CHANGEkeyword. Followed by a colon, space, and description. For example:

$ git commit -m "feat(OAuth): add scopes for OAuth apps

BREAKING CHANGE: environment variables now take precedence over config files."

- An exclamation mark

!can be added before thetype/scopeto get attention and emphasize that the commit contains breaking change.

So now, after the project is using Conventional Commits we have:

- Human readable project history

- measuring and classification of effort

- way to use Semantic Release to automate versioning and automatically generate changelogs for the project with semantic-release plugins.

- way to use Commit Lint to lint commit messages according to Conventional Commits.

- and finding, filtering and analyzing the commit history is also more straightforward when you can use the regex or git tools to filter commits by

typeorscope(or both).

Some useful links

https://www.conventionalcommits.org/en/v1.0.0-beta.4/#specification

https://github.com/angular/angular/blob/master/CONTRIBUTING.md#commit

https://github.com/conventional-changelog/commitlint/tree/master/%40commitlint/config-conventional

https://karma-runner.github.io/0.10/dev/git-commit-msg.html

https://electronjs.org/docs/development/pull-requests#commit-message-guidelines

https://chris.beams.io/posts/git-commit/#seven-rules

https://codito.in/semantic-commits-for-git