OKRs

It’s like goals served in a fractal manner. — Eric, founder of Pebble

https://twitter.com/naval/status/219480682676756480

Even with a stellar team, chock-full of strong expertise, it’s hard to create a long-lasting company. The tenacious workers that make it through the initial challenges of forming a company face the complicated task of aligning the company towards a common goal that seems ever-changing (in a competitive and fickle landscape).

Do you ever wonder how successful companies continue to navigate and grow? I often wondered how the companies I admired knew what direction to go — and it became apparent that the trick was being almost irresponsibly aggressive in growing key objectives with a talented group of people.

When Punchd joined Google in 2011 I was exposed to a key organizational goal-setting tool called Objective & Key Results, or OKRs, that helped transform Google from its humble roots into the behemoth that influences the world in nearly all aspects today.

Inspired by this concept (and my interactions with it while working at Google) I wrote a template for writing OKRs to help others begin using OKRs at their companies in early 2013.

“Startup OKRs” returns my Google Doc as one of the first few results.

Since publishing this document I’ve been delighted to see ~20 people (or anonymous animals) perusing my template at any given time. I’ve managed to get pretty decent search ranking without doing anything.

Here are my thoughts on why OKRs are awesome, how they work and why they are so important that you should start using them now.

What are OKRs?

OKR is an abbreviation for Objective & Key Result. The concept was invented at the Intel Corporation and is widely used amongst the biggest technology companies in the world including Google and Zynga.

OKRs are meant to set strategy and goals over a specified amount of time for an organization and teams. At the end of a work period, your OKRs provide a reference to evaluate how well you did in executing your objectives.

Spending a concerted effort in identifying your company strategy and laying it out in a digestible way with OKRs can truly help your employees see how they are contributing to the big picture and align with other teams.

Objectives

Any initiative has an objective. The goal of setting an objective is to write out what you hope to accomplish such that at a later time you can easily tell if you have reached, or have a clear path to reaching, that objective.

Choosing the right objectives is one of the hardest things to do and requires a great deal of thinking and courage to do well.

Key Results

Assuming your Objectives are well thought through, Key Results are the secret sauce to using OKRs. Key Results are numerically-based expressions of success or progress towards an Objective.

Expectations that are numerically defined produce results that can be quantitatively measured and scored.

The important element here is measuring success. It’s not good enough to make broad statements about improvement (that are subjectively evaluated). We need to know how well you are succeeding. Qualitative goals tend to under-represent our capabilities because the solution tends to be the lowest common denominator.

e.g If I create a goal to “launch new training for the sales team” I might do that for one sales member. If I alternatively make a Key Result of “train 50 sales team members” and only train 10, I’ve still 10x-ed my original goal.

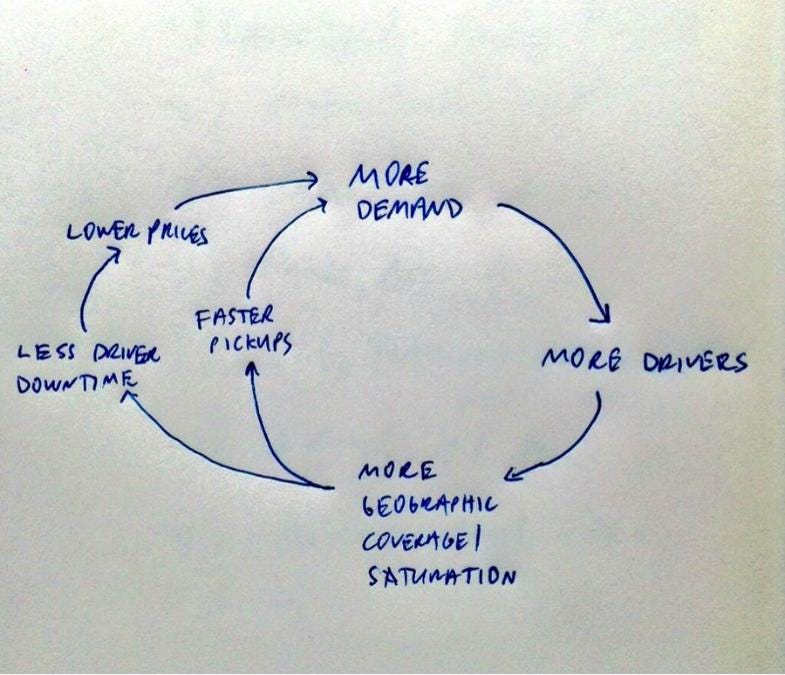

Example — Uber

There is this wonderful paper napkin plan of Uber’s path to growth. When I first saw it, it made so much sense:

Objective Gold.

For now I’d like to make the assumptions that Uber’s other aspirations are separate from what we’re evaluating here. Let’s make the assumption that pushing this model forward was the primary goal for the company in 2014.

How can OKRs help make this function real?

They apply a numerical framework to this growth strategy so teams know what’s important and what to drive:

Objective: Increase Drivers in System

- Increase driver base in each region by 20%

- Increase driver average session to 26 hours / weekly in all active regions

Objective: Increase Geographic Coverage of Drivers

- Increase coverage of SF to 100%

- Increase coverage for all active cities to 75%

- Decrease pickup time to < 10 mins in any coverage area during peak hours of usage

Objective: Increase Driver Happiness

- Define and measure driver happiness score

- Increase driver happiness score to 75th percentile

Applying numerical goals to areas of importance means:

- We communicate what’s important to the company

- We apply easily understood goals with numerical success criteria

- We begin to measure based on our goals as opposed to raw organic (or paid) growth.

Solving how these OKRs are met is up to the talented teams and individuals at Uber who think about this day in and out.

Edit: A kind gentlemen pointed out that defining driver happiness is not numerical. In my view, selecting what to measure is as important as the forward measurement itself. Sometimes that can be at an Objective level, and sometimes it’s important but not that important. OKRs are an imperfect tool, and sometimes they need to bend for the greater good.

Example — YouTube

Say your goal is to increase the total usage time of Google products. The tricky part is finding the right metrics in which to progress. Understanding your business is key in being able to identify key growth nuances and folding those nuances into company objectives.

Similar to Facebook, YouTube wants viewership, measured in minutes, to go up because a fixed percentage of that viewership is ads. So as total time goes up so do revenues, predictably.

Objective: Increase average watch time per user.

Assuming you’ve been tracking watch time the key results could be to:

- Increase total viewership time to XX minutes daily

- Expand native YT application to 2 new OSs

- Reduce video loading times by X%

In this case the Key Results may reveal part of the strategy to increase watch time. The first key result sets a numerical goal to hit for the objective. Having this number is crucial (and theoretically could be included in the objective itself) to score the outcome of this objective.

If the key result is reached easily the number was not aggressive enough. Alternatively if the goal is attempted and falls well short it’s important to revise expectations in the next round of OKRs.

It is recommended to always shoot for stretch objectives. If you are consistently hitting your goals you are undershooting your capabilities. At Google, we strive to achieve a 0.7 score of our stated Objectives.

The Key Results are flexible to allow for a number of solutions. Sometimes they embed the plan for reaching the objective:

One option is to expand the Serviceable Obtainable Market by adding Windows phone users who then would add to watch time.

Users might have been shown to not watch videos if they take too long to load, or have unpredictable uptime. Thus YouTube might make serious investments to reduce loading times by supporting edge caches of video. In these scenarios a Key Result might need to become it’s own separate Objective to fully capture the requirements.

OKRs represent a devilishly simple communication tool. If used well you will be responsible for incredible progress.

OKRs as a communication framework

As you might have guessed by now, effective OKRs are widely shared and meant to be understood by teams and individuals.

In that regard, they can serve as a communication framework for directing groups to solve complex challenges with constraints. As a communication tool, OKRs bring two key things to an organization:

- Easily digestible direction such that every member in the organization understands how they contribute to the mission; aka focus

- Expectations amongst teams and their individual members; aka accountability

Defining measurable results becomes easier as you learn what you should be measuring and what ultimately matters for your business. In my work with founders I find that the quality of OKRs has a good correlation with their understanding of their business. Blindly going for growth without understanding the reasons behind specific metrics (revenue drivers, hypothesis testing) can be damning.

I began to use the OKR framework to help my friends’ startups, which varied in size from 4–100+ people, because of the tool’s practicality and straightforwardness. I found my friends running into two challenges as their companies grew:

- What should we do next — and how do we know if it’s working?

- What is an effective way to align the organization towards a common goal? (aka: better direction setting)

In the first scenario OKRs forces the measurement of any company endeavor. Ideally this optimizes the input efforts because things that are working will be continued (and grow in scope), while the areas that get dropped or do not work well will be reevaluated or canned.

In the second scenario, which is notoriously hard to do well, OKRs provide a framework to explain the company’s goal(s) and provide enough objectives that can be broken down into smaller components for the many teams involved in making it a reality. The better you can state your goals the easier your teams can figure out what needs to happen and how to get there.

This may seem simplistic — too good to be true, but I’ve found just going through the exercise of either defining OKRs, or reworking current company plans into OKRs to be a highly effective evaluation tool.

The Template & Deployment

Can a Google doc really do all of this for our company?

I would also be skeptical, if I hadn’t seen the same be done at Motorola shortly after Google acquired the company in 2012. The latest Moto X, Moto 360, and other products had used OKRs to help us identify our strategic goals and how we’d measure ourselves on their success.

Our fast phone update strategy was an OKR, and was well-received by nearly everyone (except the other laggard OEMs):

This isn’t a surprising move from Motorola, considering the company has been able to provide swift Android updates to some of its Android devices in the recent past, especially for the Moto X and Moto G handsets. — Chris Smith, BGR

Goal setting and planning was not a new concept at Motorola, but OKRs as a framework was new and we managed it in the software organization entirely through Google docs.

Hundreds of engineers worked tirelessly to implement the latest Android drops into our phones (at all tiers) so that users had the best version of Android available. We notoriously beat the Nexus team to their own updates on some devices.

A 200 person group started to turn a ship around in a brand new direction with a bunch of Google docs as our guiding light.

And with the right tools and strategy you can do it as well.

The template is identical to the one I use alongside my teams at Motorola and Google and operate on a quarterly cycle. Our leadership presents us both annual and quarterly goals from which we derive our OKRs. Having leadership think in terms of years (when they can) is important to keep the big picture direction intact.

Without further ado, the template:

The template is an example of a real (but anonymous) OKR implemented at a company. You can copy this template and modify it to fit your needs. It should be widely distributed to your team and serve as a reference when making decisions around strategy and goals.

I am convinced it is one of the most profound and powerful tools that anyone and everyone should be using.

Closing Thoughts & Nuances

I say this to a lot of founders. You understand your business your areas of expertise and hopefully where you suck. Sometimes you need to just say those things to someone and hear that person agree with you to believe it.

OKRs are meant to help you communicate with your company on how to move forward and win. The better you understand your goals and how to get there the more effective and precise your objectives will be — and same with your outcomes.

Strong OKRs make it easy for everyone to know how they contribute.

So it’s important to remember that OKRs should conform to help you and not the other way around.

Don’t half-ass OKRs. Do them, or don’t.

I’ve seen plenty of leadership not put in the time to do their OKRs well. They are busy hiring, dealing with immediate fires, or any of the other work that removes blocks of critical thinking from their schedule.

The best leadership doesn’t break when it comes to setting strategy and key initiatives. They put in the time and sit around for hours discussing ideas with their top lieutenants because they know that an extra day spent planning will reap rewards down the line if executed properly.

Taking the time to plan OKRs and adequately assess them after each time period is a sign of respect for your colleagues and employees. It means you respect the placement of their time and efforts.

If you’re going to do OKRs because they look easy you’re making a mistake.

They are only as effective as your commitment to using them and your efforts in deriving them.

Choosing and calculating your Metrics

There’s something I haven’t written much about in this text which is what should my objectives be?

The answer to that question is difficult because each business is different and requires a unique strategy in their market. I find that those who know their business the best come up with the best OKRs because they understand what they must ignore so they fight the useful fights instead of blindly looking for growth or other seemingly significant but useless metrics.

Sometimes applying critical thought for an extended period of time going through the OKR process will actually teach you about something you thought was important, but is not.

I’d love your feedback on the template or my thoughts. Please leave a note or shoot me 140 @niket.

I hope you found this useful and good luck.

Thanks to Nat Welch, Xander Pollock, Mike Heath, Eric Migicovsky and Alex Baldwin for reading and improving drafts of this post. And many thanks to the people who helped shape or put up with my ideas as they materialized.

This post is part of a series of posts made towards a commitment to open source a set of tools I’ve been developing over the past few years.