The radiating programmer

You are an individual contributor at heart. You like writing code and solving technical problems. You dislike meetings and ceremony. Here’s what you can do to maximize what you like and minimize what you don’t: radiate information.

The daily standup meetings that Scrum popularized have bad press for a reason. The daily periodicity is way too much. And using a recurring meeting to give people a chance to catch up is atrociously disruptive and inefficient. But the questions themselves make sense: What did you do? What are you going to do? Are there any blockers? You should aim to communicate that information routinely, just not in a meeting.

When building software, everyone involved must adjust what they do as they learn about the problem. And that learning happens — in no small part — through the people doing the job. If they only offer their output, someone else needs to extract those lessons to make adjustments. That’s precisely when the bad kind of ceremony — the intrusive, disruptive, and lousy one — leaks into the process.

It’s indeed by comparison that radiating information shines: instead of having someone pulling information from you, you push the information out there for everyone. It might look subtle, but there is a significant difference: the control remains on your side, not anyone else’s.

One can argue that whenever you communicate, you radiate information. But I am talking about something more intentional here. In my daily job, I find three recurring scenarios:

- Communicate what you have been up to periodically.

- Communicate progress on projects.

- When making decisions, to give others a chance to intervene without being blocked.

Next, I will show examples from our own Basecamp. The underlying idea is not tied to any tool, but if you are familiar with 37signals’ communication philosophy, you won’t find it surprising that Basecamp comes with first-class support for it.

What have you worked on?

This is the backbone. We use a check-in so that everyone can answer “What have you worked on?” at least twice per week. I wrote about this question some time ago. You answer these asynchronously, whenever you want, with the style and level of detail you prefer, and everyone in the company can read everyone else’s answers.

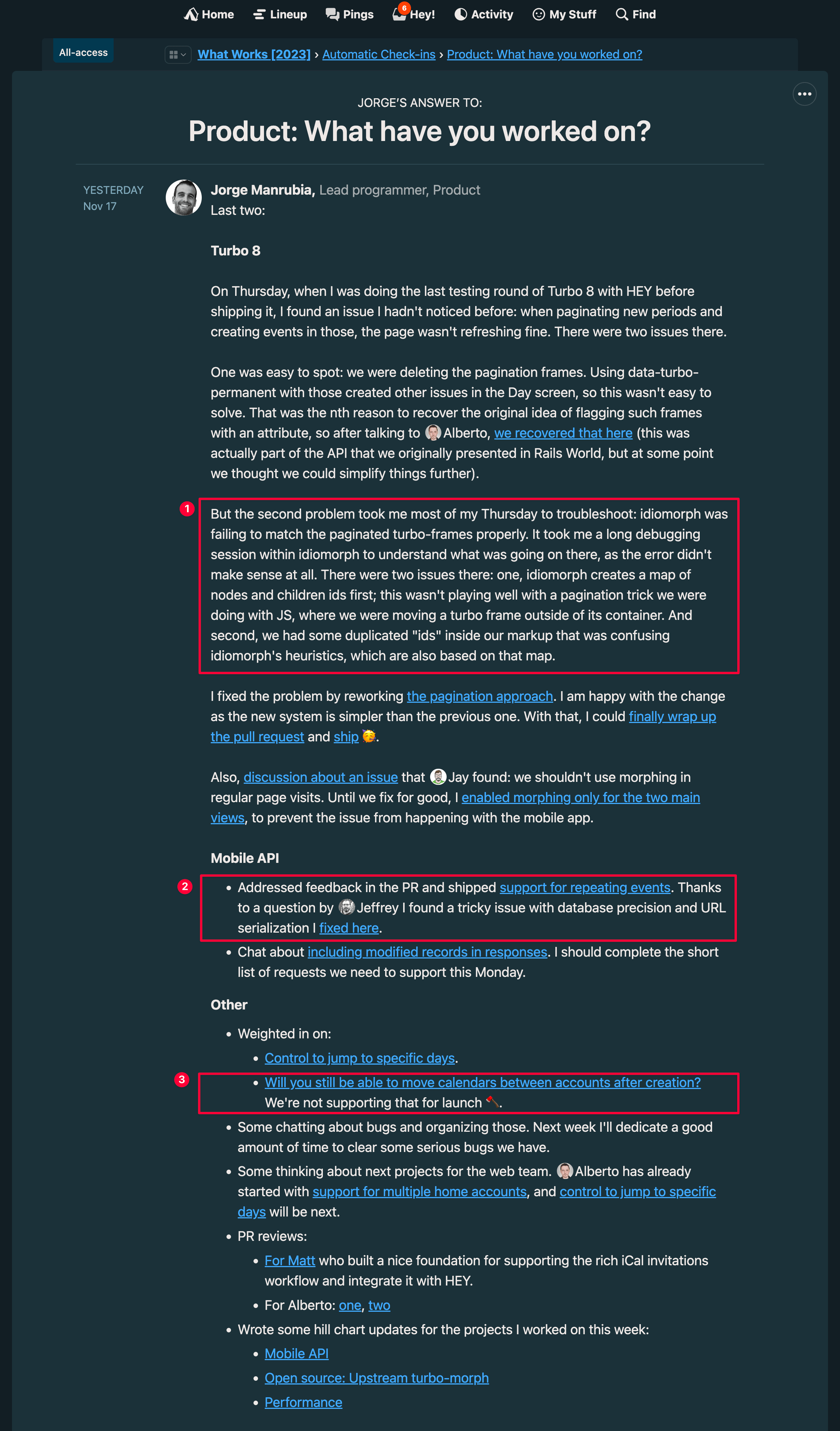

Here’s the last answer I wrote:

Answer to “What did you work on?”

I have highlighted three sections to illustrate how others could benefit from the information I shared:

- An unexpected problem that affected what I could accomplish this week.

- Something I learned that other programmers might find useful.

- Some scope hammering that could be interesting to folks making product calls.

Communicating progress on projects

Tools can help, but it is very hard to get a high-level picture of how a project is progressing unless another human — preferably the one doing the job — helps. And no, I don’t think AI will change that anytime soon.

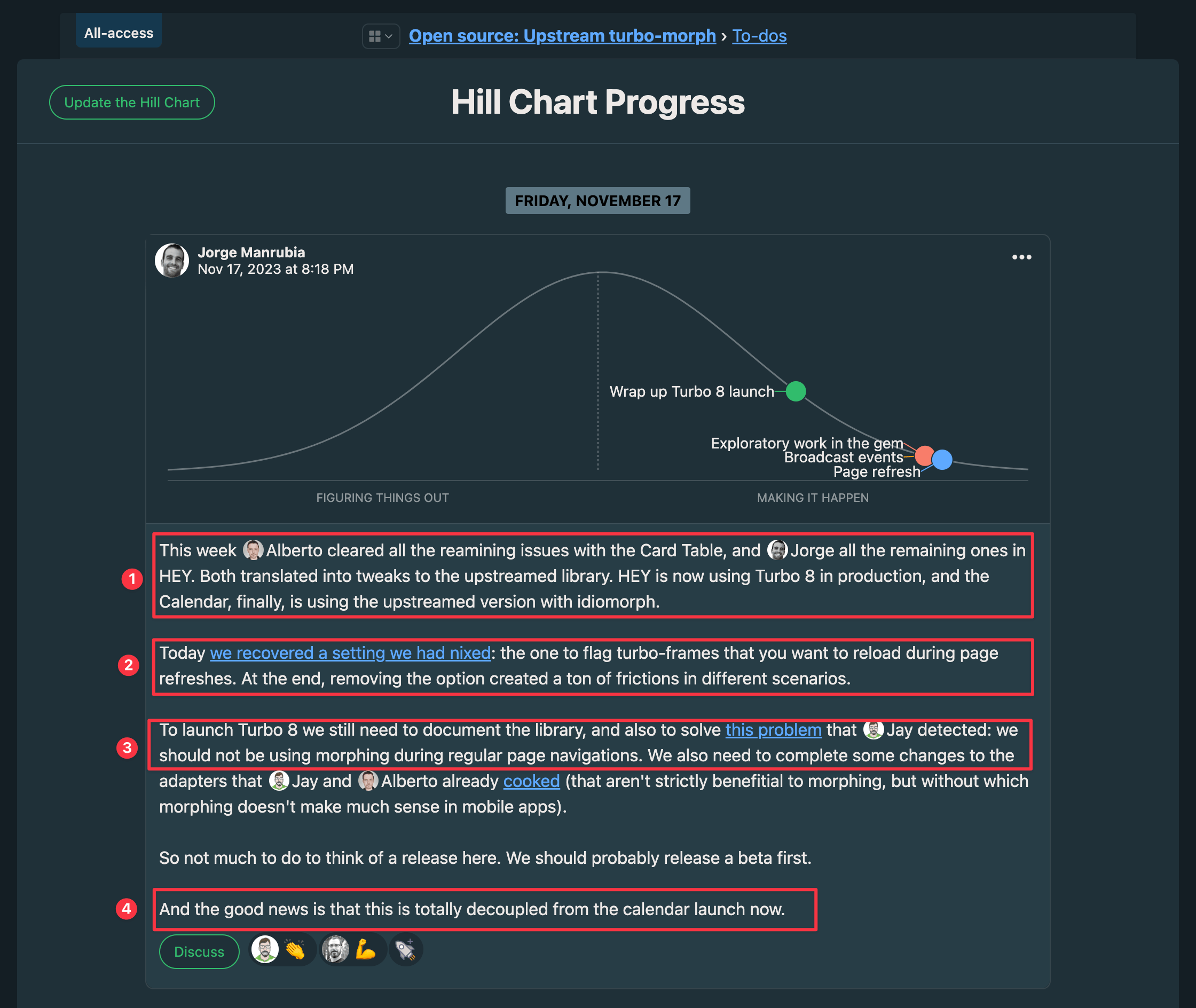

Our preferred way to show progress in Basecamp is through Hill Charts updates. They combine a high-level completion gauge with a textual description. Here’s the last one I wrote:

Answer to “Hill chart update”

Again, different people in the company can get different things from the update:

- Progress since the last update.

- A problem that resulted in recovering some API we had removed.

- Something we discovered that implies additional work.

- How does this affect, or doesn’t, the Calendar launch?

Non-blocking decisions

I have written about how you should avoid blocking yourself when working remotely. When you need input from others to make a decision, you can often make the decision yourself while informing about it. Others can intervene if they want, or you can move forward if they don’t.

Here’s an example from last week. I had a question about the mobile API I wanted to check with the team. I used my best judgement to make a call and looped them in. I was happy to change the approach based on the answer, but I didn’t put myself in a self-blocking situation waiting for it.

Collaborating without blocking yourself

Conclusion

Information radiation can look like a bureaucratic practice on the surface, but it is actually a protection against that. Think of the alternatives for the examples I referenced:

- Catchup meeting to see what’s left for launching Turbo 8.

- Chat mention to someone in the mobile team to synchronously discuss the API response format.

- 1-1 with a manager to communicate how the stuff we discovered with Turbo affects the Calendar launch.

- Quick call with a designer to decide whether to implement the feature we decided to nix.

Exaggerated? That’s exactly how work looks in a lot of places. If you need a meeting, make sure it’s not one you could have avoided by radiating information. Think of this meeting could have been an email but with a process where emails flow proactively, by design.

As a programmer, you can add much value by summarizing your work. You can share lessons learned, struggles, unexpected turns, motivations, and, more broadly, how things move forward. No tool or automatic report can do that. Many people can benefit; you can help others and receive help. You favor making decisions based on how reality looks, which is an essential trait for any non-predictable endeavor such as software development. And ultimately, it brings clarity to what you do, which counterweights the intrinsic opacity of spending your days writing code.

Radiating information is not free; it takes time. You need to find a balance that makes sense. I estimate I spend one or two hours per week writing what I did or project updates. I usually leave it for the last part of my day. It doesn’t interrupt my main focused work, and it doesn’t happen every day. It’s also a muscle to train. The more you do it, the easier it gets.

And whenever it feels like a chore, I remind myself that it is a chore that lets me spend most of my time doing what I like.